How to Make Artificial Persons:

Hobbes's Dramatistic Theory of Interaction and of Political

Representation

We will deal

here with Thomas Hobbes's dramatistic theory of social interaction and

of political representation, expounded in Part I of Leviathan.

The dramatistic dimension of Hobbes's anthropology is a crucial link

between his theory of the body, of perception and communication, and

his theory of the body politic, of political authority and of

representation.

Many aspects of the dramatistic theory of the self and of communication

developed by the

symbolic interactionists, such as George Herbert Mead and

Erving Goffman, are

prefigured in chapter XVI of Part I of Leviathan. Thomas Hobbes's

dramatism no

doubt owes much to the dramatism of Shakespeare and his contemporaries,

but Hobbes takes it to a new level of explicit reflection, theorizing

the

notions of person both in everyday action and with reference to the

conventionally created persons in legal fictions. This is a crucial

notion in his political philosophy, as can be seen in the very notion

of the Leviathan, the State as the giant made of many people, as an

artificial

person. Dramatism is

central, then, both to Hobbes's psychology and to his political theory,

which are of one piece. Political representation as an

institutionalized role-playing is a cornerstone of Hobbes's

understanding of the political order.

Chap.

XVI

Of PERSONS,

AUTHORS, and

things Personated

[A Person what] A PERSON, is he

whose

words or actions are considered, either as his own, or as representing

the words or actions of an other man, or of any other thing to whom

they are attributed, whether Truly or by Fiction.

[Persons Naturall, and Artificiall] When they are considered as

his owne, then he is called a Naturall

Person: And when they are

considered as representing the woers and actions of an other, then he

is a Feigned or Artificiall person.

[The word Person, whence] The

word Person is latine: instead whereof the Greeks have prósopon, which signifies the Face, as Persona in latine signifies the disguise, or outward appearance of a man,

counterfeited on the Stage; and somtimes more particularly that part of

it, which disguiseth the face, as a Mask or Visard: And from the Stage,

hath been translated to any Representer of speech and action, as well

in Tribunalls, as Theaters. So that a Person,

is the same that an Actor is,

both on the Stage and in common Conversation; and to Personate, is to Act, or Represent himselfe, or an other; [Note well Hobbes's

move here: in being "natural persons" we are not bypassing the question

of representation: instead, we are representing ourselves, somewhat

like Shakespeare's King Harry on the stage of history, "playing

himself", playing his own role in his own person, as Shakespeare says

in the prologue to Henry V]

and he that acteth another, is said to beare his Person, or act

in his name; (in which sence Cicero

useth it where he saies, Unus

sustineo tres Personas; Mei, Adversarii, & Judicis, I beare

three Persons; my own, my Adversaries, and the Judges; and is

cal[81]led in diverse occasions, diversly; as a Representer, or Representative, a Lieutenant, a Vicar, an Attorney, a Deputy, a Procurator, an Actor, and the like. [Here Hobbes shows,

on the one hand, that the spontaneous function of representation has

given rise to these roles, institutions or professions, on the other,

he also calls attention to our spontaneous theory of "personation" or

representation, understood through common language and the ordinary

social interaction in dealing with these professions, a pre-theoretical

awareness which he brings to consciousness and makes fully theoretical

here, partly by pointing out the historical genesis of the social

function, buried in the etymology of these terms.]

Of Persons Artificiall, some have their words and actions Owned by those whom they represent.

[Actor, Author,] And then the

Person is the Actor; and he

that owneth his words and actions, is the AUTHOR: In

which case the Actor acteth by Authority. [Cf. here Erving Goffman's hierarchy of

persons, in Forms of Talk: the principal, the author, and the

animator—a slightly different division of roles: Goffman's 'principal'

is the one invested with final authority, and hence equivalent to

Hobbes's 'Author', e.g. the promoter or sponsor of a publication, or

the producer of a film; the author of a text and its animators

(narrators, 'actors', characters, etc.) are mere ghost writers or

speakers, and thence 'Actors' acting by Authority.] For that

which in speaking of goods and possessions, is called an Owner, and in latine Dominus, in Greeke Kyrios; speaking of Actions, is

called Author. And as the Right of possession, is called Dominion; [Authority] so the Right of doing

any Action, is called AUTHORITY. So that by Authority,

is alwayes understood a Right of doing any act: and done by Authority, done by

Commission, or Licence from him whose right it is.

[Covenants by Authority, bind the

Author]

From hence it followeth, that when the Actor maketh a Covenant by

Authority, he bindeth thereby the Author, no lesse than if he had made

it himselfe; and no lesse subjecteth him to all the consequences of the

same. And therefore all that hath been said formerly, (Chap. 14.)

of the nature of Covenants, between man and man in their naturall

capacity, is true also when they are made by their Actors,

Representers, or Procurators, that have authority from them, so

far-forth as is in their Commission, but no farther.

And therefore he that maketh a Covenant with the Actor, or Representer,

not knowing the Authority he hath, doth it at his own perill. For no

man is obliged by a Covenant, whereof he is not Author; nor

consequently by a Covenant made against, or beside the Authority he

gave.

When the Actor doth any thing against the Law of Nature by command of

the Author, if he be obliged by former Covenant to obey him, not he,

but the Author breaketh the Law of Nature: for though the Action be

against the Law of Nature; yet it is not his: but contrarily; to refuse

to do it, is against the Law of Nature, that forbiddeth breach of

Covenant. [Now

Hobbes is being rather inconsistent—good logic would lead us to see,

instead, that the Law of Nature cannot work this way. Although of

course this ethics of action is often sustained in practice, and not

just by Hobbesians, in those political systems which want to emphasize

and leave unquestioned the absolute submission of persons to other

persons, rather than to the law. — J.A.G.L.]

[The Authority is to be shewne]

And he that maketh a Covenant with the Author, by mediation of the

Actor, not knowing what Authority he hath, but onely takes his word; in

case such Authority be not made manifest unto him upon demand, is no

longer obliged: For the Covenant made with the Author, it is not valid,

without his Counter-assurance. But if he that so Covenanteth, knew

before hand he was to expect no other assurance, than the Actors word;

then is the Covenant valid; because the Actor in this case maketh

himselfe the Author. And therefore, as when the Authority is evident,

the Covenant obligeth the Author, not the Actor; so when the Authority

is feigned, it obligeth the Actor onely; there being no Author but

himselfe.

[Things personated, Inanimate]

There are few things, that are incapable of being represented by

Fiction. Inanimate things, as a Church, an Hospital, a Bridge, may be

Personated by a Rector, Master, or Overseer. But things Inanimate,

cannot be Authors, nor therefore give Authority to their Actors; Yet

the Actors may have Authority to procure their mainte[82]nance, given

them by those that are Owners, or Governours of those things. And

therefore, such things cannot be Personated, before there be some state

of Civill Government.

Likewise Children, Fooles, and Mad-men that have no use of Reason, may

be Personated by Guardians, or Curators; but can be no Authors (during

that time) of any action done by them, longer then (when they shall

recover the use of Reason) they shall judge the same reasonable. Yet

during the Folly, he that hath right of governing them, may give

Authority to the Guardian. But this again has no place but in a State

Civill, because before such estate, there is no Dominion of Persons.

[False Gods;] An Idol, or meer

Figment of the brain, may be Personated; as were the Gods of the

Heathen; which by such Officers as the State appointed, were

Personated, and held Possessions, and other Goods, and Rights, which

men from time to time dedicated, and consecrated upon them. But idols

cannot be Authors: for an Idol is nothing. The Authority proceeded from

the State: and therefore before introduction to Civill Government, the

Gods of the Heathen could not be Personated.

[The true God] The true God

may be Personated. As he was; first, by Moses; who governed the Israelites,

(that were not his, but Gods people,) not in his own name, with Hoc dicit Moses; but in Gods name,

with Hoc dicit Dominus. [As

happens elsewhere in Leviathan, here Hobbes enacts with his

unquestioning acceptance of the British status quo and of the truth of

the Christian religion, the principle he is explaining: that of the

state's legitimacy to establish what is to be publicly believed, or

published, and thus his treatise does what it preaches, Q.E.D.—JAGL]

Secondly, by the Son of man, his own Son our Blessed Saviour Jesus Christ,

that came to reduce the Jewes, and induce all Nations into the Kingdome

of his Father; not as of himselfe, but as sent from his Father. And

thirdly, by the Holy Ghost, or Comforter, speaking, and working in the

Apostles: which Holy Ghost, was a Comforter that came not of himselfe;

but was sent, and proceeded from them both.

[A Multitude of men, how one Person]

A Multitude of men, are made One

Person, when they are by one man, or one Person, Represented; so that

it be done with the consent of every one of that Multitude in

particular. For it is the Unity of

the Represented, that maketh the Person One. And it is the Representer that

beareth the Person, and but one Person: and Unity, cannot otherwise be

understood in Multitude.

[Every one is Author] And

because the Multitude naturally is not One, but Many;

they cannot be understood for one; but many Authors, of every thing

their Representative faith, or doth in their name; Every man giving

their common Representer, Authority from himselfe in particular; and

owning all the actions the Representer doth, in case they give him

Authority without stint: Otherwise, when they limit him in what, and

how farre he shall represent them, none of them owneth more, than they

gave him commission to Act. [Who'd

have expected Hobbes to theorize the best of possible worlds. In

practice, demagogical manipulation, propaganda, secret wheels

behind wheels, and plain ignorance and irresponsibility on the part of

the electors are the very substance of political representation—JAGL.]

[An Actor may be Many men made One by

Plurality of Voyces]

And if the Representative consist of many men, the voyce of the greater

number, must be considered as the voyce of them all. For if the lesser

number pronounce (for example) in the Affirmative, and the greater in

the Negative, there will be Negatives more than [83] enough to destroy

the Affirmatives; and thereby the excesse of Negatives, standing

uncontradicted, are the onely voyce the Representative hath.

[Representatives, when the number is

even, unprofitable].

And a Representative of even number, especially when the number is not

great, whereby the contradictory voyces are oftentimes equall, is

therefore oftentimes mute, and uncapable of Action. Yet in some cases

contradictory voyces equall in number, may determine a question; as in

condemning, or absolving, equality of votes, even in that they condemne

not, do absolve; but not on the contrary condemne, in that they absolve

not. For when a Cause is heard; not to condemne, is to absolve: but on

the contray, to say that not absolving, is condemning, is not true. The

like it is in a deliberation of executing presently, or deferring till

another time; For when the voyces are equall, the not decreeing

Execution, is a decree of Dilation.

[Negative voyce] Or if the

number be odde, as three, or more (men, or assemblies;) whereof every

one has by a Negative Voice, authority to take away the effect of all

the Affirmative Voices of the rest, this number is no Representative;

because by the diversity of Opinions, and Interests of men, it becomes

oftentimes, and in cases of the greatest consequence, a mute Person,

and unapt, as for many things else, so for the government of a

Multitude, especially in time of Warre.

Of Authors there be two sorts. The first simply so called; which I have

before defined to be him, that owneth the Action of another simply. The

second is he, that owneth an Action, or Covenant of another

conditionally; that is to say, he undertaketh to do it, if the other

doth it not, at, or before a certain time. And these Authors

conditionall, are generally called SURETYES, in Latine Fidejussores, and Sponsores; and particularly for

Debt, Praedes; and for

Appearance before a Judge, or Magistrate, Vades.

[Hobbes

does not contemplate a frequent case of party politics—when all the

supposed "voyces" are really only so many counters to be manipulated by

the leader of the faction to carry out a hidden programme, and the body

of representatives is to decide through a few voices of unequal weight

and uncertain solidity, not by a number of voices of the same weight].

Hobbes's

examination of

political representation is of course central to his political theory.

Political power rests (in Hobbes before Locke or Montesquieu or

Rousseau) on a covenant or social contract. Therefore a theory of the

contract is essential. The King (in his role as the Leviathan)

represents the whole nation, and is therefore an "Artificial Man".

Political power in a commonwealth requires this fundamental act of the

delegation of power, or representation, the capacity to "personate"

others, or to act for them and represent them. No wonder the

political significance of this passage has attracted most of the

attention of commentators.

But there is a more basic phenomenological fenomenon lying at the

basis

of this theory of political representation, one which is of a piece

with Hobbes's theory of the world as a construction, as something

actively constituted by the human mind, not merely passively absorbed

or received by it. The very notion of the human subject is mediated by

representation, by this active "playing ourselves". Perhaps this is the

key insight to be found in Hobbes's dramatistic theory of society and

of politics:

"that

a Person,

is the same that an Actor is,

both on the Stage and in common Conversation; and to Personate, is to Act, or Represent himselfe, or an other."

A simple yet profound insight. We

can play many parts in the social theatre.

That we play ourselves as a matter of fact may be a common

presupposition, but one which often requires clarification. In which

capacity are we acting? As a King, or as a private citizen? In our

office as one more member of the commonwealth, or with our magistrate's

hat? We find here, in nuce, a

theory of social life as role-playing. A person is not simply a person,

even if one is trapped in the body of the actor: a person is a role to

be played, and there are rules to the game of personating others, just

as there are limits to one's own self-personation —at the very least,

the mutual limits which these living theatres set to each other.

—oOo—

This dramatistic theory of action

and of personality (in which roles

are available as something to assume, either in acting as one's own

person, i.e. as a private individual, or in acting in representation of

another person, is then developed into his theory of political

representation. There are two passages which provide a major key

to the whole book, as is evident from their explanatory allusion to the

title. In many books, especially those with an enigmatic title, a

crucial passage reveals, clarifies or undescores the meaning of the

title. Here is Leviathan's

explanation of its title, Leviathan,

which is also an explanation of a gigantic maneuver of "personation", a

mode of dramatistic interaction. Developing the reasoning prepared from

the very first words of The

Introduction

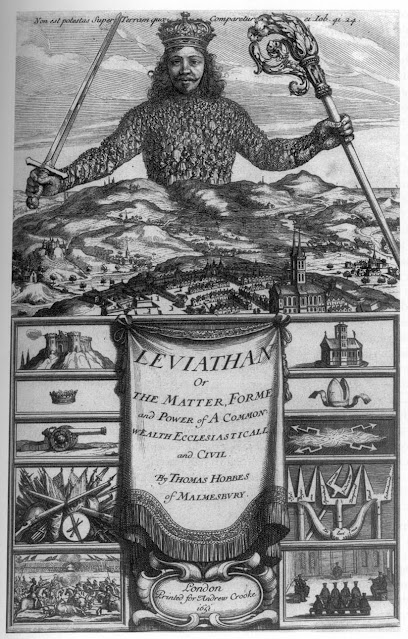

to the volume, Hobbes explains the making of a Gigantic Artificial

Animal, a Leviathan (the one portrayed in the famous frontispice to the

book).

From the Introduction:

"Nature (the Art whereby

God hath made and governes the World) is by the Art of

man, as in many other things, so in this also imitated, that it can

make an Artificial Animal. (...) For by Art is created that great LEVIATHAN

called a COMMON-WEALTH, or STATE,

in latine CIVITAS)

which is but an Artificiall Man; though of greater stature and strength

than the Naturall, for whose protectio and defence it was intended; and

in which ,the Sovereignty is

an Artificiall Soul, as

giving life and motion to the whole body (...)." (81).

And from

II.17, "Of Common-wealth", another key

passage. Note that the

"personation" whereby the political power is constituted is a

collective action, and that the role of the soul of the commonwealth

may be performed by a monarch (the theory usually associated to Hobbes

as a theorist of absolute monarchy) or by an "assembly", a body of

representatives.

The Generation of a Common-wealth. The

only way to erect such a Common Power, as may be able to defend them

from the invasion of Forraigners, and the injuries of one another, and

thereby to secure them in such sort, as that by their owne industrie,

and by the fruites of the Earth, they may nourish themselves and live

contentedly, is, to conferre all their power and strength upon one Man,

or upon one Assembly of men, that may reduce all their Wills, by

plurality of voices, unto one Will: which is as much as to say, to

appoint one man, or Assembly of men, to beare their Person; and every

one to owne, and acknowledge himselfe to be Author of whatsoever he

that so beareth their Person, shall Act, or cause to be Acted, in those

things which concerne the Common Peace and Safetie; and therein to

submit their Wills, every one to his Will, and their Judgements, to his

Judgement. This is more than Consent, or Concord; it is a reall Unitie

of them all, in one and the same Person, made by Covenant of every man

with every man, in such manner, as if every man should say to every

man, I Authorise and give up my

Right of Governing my selfe, to this Man, or to this Assembly of men,

on this condition, that thou give up thy Right to him, and Authorise

all his Actions in like manner. This done, the Multitude so

united in one Person, is called a COMMON-WEALTH, in

latine CIVITAS. This is the Generation of that great LEVIATHAN,

or rather (to speake more reverently) of that Mortall God,

our peace and defence. For by this Authoritie, given him by every

particular man in the Common-Wealth, he hath the use of so much Power

and Strength (88) conferred on him, that by terror thereof, he is

inabled to forme the wills of them all, to Peace at home, and mutuall

ayd against their enemies abroad. (The

Definition of a Common-wealth). And in him consisteth the

Essence of the Common-wealth; which (to define it.) is One

Person, of whose acts a great Multitude, by mutuall Covenants one with

another, have made themselves every one the Author, to the end he may

use the strength and means of them all, as he shall think expedient,

for their Peace and Common Defence.

And he that

carryeth this Person, is called SOVERAIGNE, and said to

have Soveraigne Power; and

every one besides, his SUBJECT.

(227-28)

It is clear from the above that both the Sovereign and the Subject are masks or "persons"

that are worn, or dramatistic roles

that are assumed, adopted—roles which are constitutive of political

identities

and political realities, in a social world whose dramatistic nature is

thereby enhanced and intensified.

—oOo—

References

Charon, Joel M. Symbolic Interactionism An Introduction, an Interpretation, an Integration. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Prentice-Hall, 1979. 7th ed. 2001. (With a chapter on Erving Goffman by Spencer Cahill).

García Landa, José Angel. "Somos teatreros: El sujeto, la interacción

dialéctica y la estrategia de la representación según Goffman." Academia 30 May 2012.

https://www.academia.edu/1603731/

2015

_____. "El interaccionismo simbólico." Trans. of Joel M. Charon's summaries in Symbolic Interactionism. In García Landa, Vanity Fea 3 April 2014.

http://vanityfea.blogspot.com.es/2014/04/el-interaccionismo-simbolico.html

2014

_____. "'Lo mismo despiertos, que soñando': Hobbes sobre la virtualidad de lo real." Ibercampus (Vanity Fea) 12 Aug. 2015.*

http://www.ibercampus.es/lo-mismo-despiertos-que-sonando-hobbes-sobre-la-virtualidad-de-lo-30985.htm

2015

_____. "How to Make Artificial Persons: Hobbes's Dramatistic Theory of Interaction and of Political Representation." Vanity Fea 10 Oct. 2015. (Preliminary version of this paper).

http://vanityfea.blogspot.com.es/2015/10/hobbess-dramatistic-theory-of.html

2015

_____. "How to Make Artificial Persons." Ibercampus (Vanity Fea) 13 Oct. 2015. Online at the Internet Archive:

https://web.archive.org/web/20200808183645/http://www.ibercampus.eu/how-to-make-artificial-people-3485.htm

2021

Goffman, Erving. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Rev. ed. Garden City (NY): Doubleday-Anchor, 1959.

_____. Forms of Talk. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 1981.

Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan. Ed. C. B. Macpherson. (Penguin Classics). Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985.

_____. "The Introduction to the Leviathan." Vanity Fea 11 Aug. 2015.

http://vanityfea.blogspot.com/2015/08/the-introduction-to-leviathan.html

Shakespeare, William. The Life of King Henry the Fifth. 1600. Online at The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (MIT):

http://shakespeare.mit.edu/henryv/

2014

Skinner, Quentin. "Hobbes and the Person of the State." Lecture a U College Dublin. YouTube (UCD - University College Dublin) 4 Jan. 2016. (State institutions as fictions and representations).

https://youtu.be/NKD7uYnCubg

2019

_____. "Hobbes's Leviathan Frontispice: Some New Observations." Video of the lecture at Warburg Institute. YouTube (WarburgInstitute) 4 Nov. 2016.

https://youtu.be/FlPf7IvOlx0

2019

—oOo—